Dopo averlo scoperto di fianco ad Almaz Ayana e Kenenisa Bekele, è bastata una sgoogolata per trovare Yannis Pitsiladis (qui CV 2015/10 e con Lieberman), in particolare la coppia di articoli del New York Times: quasi 30’000 battute a febbraio e 25’000 battute a maggio, ovviamente in inglese (nessun eco in italiano?). Qui la seconda metà del secondo pezzo, così viene voglia di tornare a quando Kenenisa aveva 10kg in più e vedere la maratona sotto le 2h no longer a matter of if but when…

An Uneasy Partnership

A software glitch left the results of Tulu’s VO2 max test unclear. Still, he did not appear to Pitsiladis to be a candidate to eventually break the two-hour barrier. Perhaps no one at the school was.

Earlier, as Pitsiladis had arrived and children had gathered around his van, he had said with disbelief and mild disappointment, “They’re all wearing something on their feet!” But Kenenisa Bekele had arranged for the trip with a phone call to Eshetu, his former coach, so Pitsiladis proceeded with the testing.

Zeru Bekele, the altitude expert, who is not related to Kenenisa, said he worried that as more schools were built in the countryside, Ethiopian children might lose something athletically by not having to run so far to class.

“It could be in Bekoji that we’re 20 years too late,” Pitsiladis said. “These are city kids.”

Perhaps he would have to go to a more remote area to find the next marathon star — higher, to 11,500 feet or 13,000 feet, where a promising barefoot teenager might live.

“Maybe the next Abebe Bikila is someone who doesn’t know about athletics and has never heard of the Olympic Games,” Pitsiladis said.

He had more immediate concerns. Pitsiladis needed a current star to give legitimacy to his provocative theories and to pique sponsor interest in the Sub2 Project, which he estimated would cost $30 million. One of Pitsiladis’s former doctoral students, Barry Fudge, had found his own willing science subject on the track in Farah, the British Olympic champion.

“Yannis would bite his right arm off to find somebody like that,” said Fudge, the head of endurance for the British track and field federation.

Pitsiladis had hoped Kenenisa Bekele would be that athlete, but months of dealing with him suggested serious obstacles might still lie ahead as Pitsiladis applied his science to elite runners in Ethiopia.

They had worked together before, as Bekele won the 10,000 meters at the 2007 world track and field championships in Osaka, Japan, and took double gold in the 5,000 and the 10,000 at the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

Even then, Pitsiladis showed a knack for experimenting in training.

To mimic the sticky summer conditions in Asia, Pitsiladis devised a thermal chamber in a home in Addis Ababa, employing heaters and kettles of boiling water while Bekele trained on a treadmill. Bekele then won his races with a punishing kick and regal eyes that seemed to intimidate others with their commanding intent.

“I really like the guy,” Pitsiladis said. “He’s the greatest athlete we’ve seen.”

Bekele made his marathon debut in Paris in 2014, finishing first and setting a course record in 2:05:04 — the sixth-fastest debut ever. But injury sideswiped him. At last year’s Dubai Marathon in the United Arab Emirates, he dropped out after 18 ½ miles, and he withdrew from the London Marathon three months later.

In July, Bekele arrived at Pitsiladis’s lab in England about 25 pounds above his competitive weight of 123. He limped when he walked. His right calf was nearly an inch smaller around than his left calf.

“I thought it was over,” Pitsiladis said. “He looked like a broken man.”

Injuries had piled up. A stress fracture in his ankle. A torn calf muscle. Strained Achilles’ tendons. It was as if a string had been pulled, yanking Bekele’s back and legs and feet, leaving his muscles out of balance.

Bekele was 33. He surely would not be the marathoner to break two hours. (“I’m very close to old,” he said.) Still, he hoped to make a comeback, to win a gold medal in the marathon or the 10,000 meters at this year’s Olympics in Rio de Janeiro and, later, to beat the world record in the marathon.

“I have that vision,” Bekele said.

If Pitsiladis could restore Bekele, Pitsiladis believed, sponsors would find the Sub2 Project a worthwhile investment.

“The whole world will believe in what I’m doing,” Pitsiladis said.

His words were hopeful, if not a sure bet.

The two men needed each other but had a complicated relationship. They seem opposites in perhaps every way but their willful determination. Pitsiladis is an extroverted scientist, Bekele a reserved and proud athlete, wary of science, or at least reluctant to change the training that brought him so much success.

So although Pitsiladis and Bekele agreed to renew their partnership, it was full of operatic uncertainty. Again and again, Pitsiladis would say, “We’re five minutes from disaster.” They could not even agree on what foods were good for runners to eat.

After a workout in September, Pitsiladis had Bekele stop his sport utility vehicle at a roadside stand in Addis Ababa and climbed out to buy bananas.

Bekele took a bite and said, “Bananas are not good sometimes.”

Pitsiladis told him: “They’re good all the time. They refuel the muscles.”

Bekele did not mean he disliked the taste.

“He thinks bananas make you fat,” Pitsiladis said.

Steps Forward (and Back)

When he visited Addis Ababa in September, Pitsiladis found that Bekele had bought into some of the prescribed rehab program but not all of it. For the first time, he was working regularly with weights and using exercise balls to strengthen his core muscles. He agreed to quit eating cakes and to adhere to a traditional, carbohydrate-rich Ethiopian diet of stews and a spongy flatbread called injera.

By late September, Bekele had dropped 11 pounds. Pitsiladis planned each meal, restricting Bekele’s calorie intake to about 1,785 per day.

“Just enough to keep you alive,” Pitsiladis told Bekele.

Yet Bekele resisted the professional techniques employed by physiotherapists for the Sub2 Project. He preferred a simple massage from a friend.

He was not the only Ethiopian runner sensitive about who worked on his legs.

“If I treat five or six athletes in a day, they believe I can’t help them anymore because I’ve taken all the bad energy from the other athletes and it will affect them in a negative way,” said Jonathan Schaible, a physiotherapist who worked with Bekele.

Part of this distrust stems from beliefs in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, athletic officials said. Religious figures known as debteras are considered fortune tellers and magical healers but are also said to summon spirits that bring misfortune and sickness. Some athletes carry protective amulets and sprinkle holy water into their workout bags, fearing that competitors could put a hex on them, Zeru Bekele said.

In late September, on his way to train at Entoto, a eucalyptus forest above Addis Ababa, Kenenisa Bekele stopped to pray at a shrine outside the octagonal, brightly painted St. Mary’s Church. He referred to debteras as priests and said he considered them “very clever.”

“If they want to make someone crazy, they can,” Bekele said. “If they want to kill you, they kill you indirectly. You can’t see, but they send some powers, some evil, to you.”

This subject had been one of intense discussion between Bekele and Pitsiladis. Last summer, when Bekele went to England for treatment, the two sat in a car and talked for hours. According to Pitsiladis, Bekele told him: “I don’t need this treatment. All I need is for the priests to O.K. me.”

If that was what he believed, Pitsiladis said he replied, perhaps Bekele should return to Ethiopia. He stayed. Pitsiladis, who is Greek Orthodox, gave him a painting of St. Raphael, who was martyred on the Greek island Lesbos.

“I wanted to demonstrate that, while religion may be important, don’t let people use religion to take over your mind,” Pitsiladis said. “You are in control of your destiny, not these people around you.”

When he left Addis Ababa in September 2015, Pitsiladis seemed more encouraged. Bekele had agreed to regular physiotherapy. He was sticking to his diet.

In early November, the tentative assurance evaporated.

Bekele wore an unfamiliar pair of shoes on a long run and strained his left Achilles’ tendon. His training became irregular. He put on weight and sometimes resisted physiotherapy.

Plans for any exotic training methods affiliated with the Sub2 Project faltered. There would be only a desperate attempt to get Bekele to the starting line of the London Marathon on April 24, a race in which he would have to give an encouraging performance to qualify for Ethiopia’s Olympic marathon team.

In January, Bekele traveled to Munich to visit a popular and controversial doctor, Hans-Wilhelm Müller-Wohlfahrt. His supporters, including the Jamaican sprint star Usain Bolt, swear by him and call him Healing Hans.

But some scientists have questioned his unconventional treatments, such as injections of Actovegin, a filtered extract of calf’s blood, along with lubricants and antioxidants. Travis Tygart, the chief executive of the United States Anti-Doping Agency, once described Müller-Wohlfahrt’s injections to ESPN as a “Frankenstein-type treatment.”

Pitsiladis accompanied Bekele to Munich, wary of the treatments. At least Müller-Wohlfahrt admonished Bekele to follow the rehab program the Sub2 Project had prescribed, Pitsiladis said. (Müller-Wohlfahrt declined a request for an interview.)

When Pitsiladis returned to Addis Ababa in February, he placed Bekele on an even stricter diet, 1,000 to 1,500 calories a day. As his weight declined, so would the pain in his heel. That was the hope, anyway. The London Marathon was only 10 weeks away.

In March, Bekele turned inward, secretive, as he sometimes had at the height of his career. He declined to tell Pitsiladis about his training regimen. He would not allow his physiotherapist to weigh him.

“He likes to make history when no one is watching,” said Mersha Asrat, Bekele’s coach.

Pitsiladis grew exasperated. But he had gotten Bekele in sufficient shape to run the London Marathon. Bekele was no longer the broken runner he had been. In an instant message, he told Pitsiladis, “Thank you for believing in me.”

Pitsiladis replied: “I believe in you 100 percent. And you need to trust me 100 percent. Then we can do it together.”

A Reward to Collect

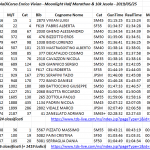

Eliud Kipchoge of Kenya eventually won in 2:03:05, the second-fastest marathon ever. While Bekele was left to run alone in the final miles, he gamely finished third in 2:06:36. The running world buzzed about his comeback. If chosen for Ethiopia’s marathon team for the Rio Olympics, he was expected to be a medal contender.

“It was nice because I come back from injury,” Bekele said. “Not bad.”

Pitsiladis hugged Bekele. Perhaps now, Bekele would more readily buy into a scientific approach to training. “Let’s see,” Pitsiladis said.

In any case, the Sub2 Project would continue. Pitsiladis planned to open a training center in Kenya and hoped to enlist Kipchoge. The International Olympic Committee had pledged funding to his lab for antidoping research, Pitsiladis said. The money could also be used for altitude research in the Sub2 Project. An American biotech firm had also shown interest, Pitsiladis said.

“I want to impact a life,” he said of his desire to break the two-hour barrier. “You’re here once. You want to do something that matters. I wanted to be an athlete in the Olympics. I didn’t do it. So how else can you make a mark that you were here? I think it’s important.”

Niente Olimpiadi per Kenenisa e così si aggiungono 6’000 battute dal Financial Times a luglio 2016 per capire qualcosa dell’uomo e dello scienziato e del finale di Kenenisa alla maratona di Berlino … In boxes behind his laptop are sachets of a sports drink he is developing with a Swedish company which he may use for his “Sub 2” marathon project once it passes tests to prove it contains no banned substances. “I can’t talk about it too much because I signed a disclosure agreement but this could be a game-changer,” he says.

https://youtu.be/wtsIYDy8Z8s?t=1h56m18s

Leave A Comment